Saturday, December 18, 2010

A Bad Week

To this point of my blog, only two of the 34 players I featured were still alive. Then this past week those two players died. The first was Bob Feller, and then a couple days later Phil Cavarretta. Their blog entries have been updated to include their death. I do not know how to blog a moment of silence, or else I would.

Thursday, December 9, 2010

#34 Babe Herman

Floyd Caves "Babe" Herman is one of long list of baseball characters, but was also one of the most feared hitters of his era. Born in Buffalo, New York, in 1903, Herman's family moved to California at an early age. As scouts caught word of the teen's hitting ability, Herman was signed to a minor league deal with Edmonton in 1921. His hitting caught the attention of Ty Cobb, who was managing the Detroit Tigers, and was invited to the club's spring training in 1922. Despite a decent showing, he could not crack into the Tigers outfield and was farmed out. In 1925, he was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers. He joined the Dodgers in 1926, and quickly became a fan favorite.

Herman batted .319 in his rookie year, with 11 home runs, a .500 slugging percentage and a 16th-place finish in the NL MVP voting. He played most of the season at first base, but his fielding was atrocious, committing 14 errors in 101 games. In 1927, he had over 21 errors, and Brooklyn moved him to the outfield. As Brooklyn's rightfielder, he quickly gained the reputation as the worst fielder in the game, committing over 10 errors in five of his first 6 seasons roaming the outfield. Fresco Thompson, a teammate of Babe's, said of Herman: "He wore a glove for one reason: because it was a league custom."

It was easy to forgive his defensive shortcomings, though, because the man could hit. He batted .340 in 1928, followed with a .381 and a .393 average, both of which placed him second in the NL Batting race. Aside from his .393 average in 1930, he also belted 35 home runs and batted in 130 runs. After 1931, he was sent to the Cincinnati Reds where he batted .326 and led the senior circuit in triples. He was then dealt to the Cubs where his career began to tail off. In 1935, he began the season with Pittsburgh, and was sent back to the Reds. In 1937, at 34 years of age, he hung it up after a 17 games with the Tigers. He played for Hollywood in the PCL until World War 2 came around. With major league rosters depleted as player were out fighting the war, Herman returned to the Dodgers in 1945 at 42 years of age. He played in 37 games before finally calling it a career. He finished with a .324 lifetime average, 1818 hits at 997 RBI.

Herman's legacy is not his hitting, or even his poor fielding. It was his colorful personality and amiable charisma. His most notable moment was occurred in 1926. With Hank DeBerry on third, Dazzy Vance on second and Chick Fewster on first with no one out, Herman lined one into the gap. DeBerry scored the go-ahead run easily. Vance held up a moment to see if the ball was to be caught by the fielder, but when he saw it was going to fall in, took off for third and headed home. Fewster was running on the pitch, and Herman was chugging away full speed. As Herman hit second base, he chose to try and stretch the double into a triple. Unfortunately for Herman, Fewster held up at third and Herman slid in well ahead of the throw, only to find Fewster standing on the base. To make matters even worse, also sliding into third base from home plate was Vance, who thought the throw was headed home and returned to third. Of course, the base went to the lead runner (Vance) and both Fewster and Herman were called out for passing the runner. Babe Herman became the only player in history to ever double into a double play. Despite this a numerous other gaffes in his career, Herman was the first player to hit for the cycle three times, and also hit the first home run in a night game in 1935.

After his playing days ended, Herman served as a scout for 22 years. In the mid 1980's, Babe suffered a series of strokes that limited his mobility. Finally, in November of 1987, Herman died of pneumonia at the age of 84.

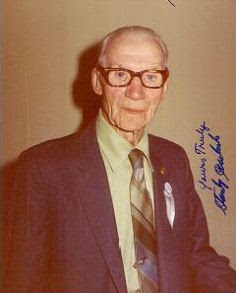

The Autograph: Herman signed whenever he was physically able, but his strokes limited his abilities by the time I got this card signed, probably at most a year before his death.

In the photo below, Babe Herman and Larry French ponder a new career behind the camera.

Thursday, November 18, 2010

#33 Billy Herman

William Jennings Bryan Herman was born in New Albany, Indiana in 1909, and broke in with the Chicago Cubs in 1931, where he became a fixture at second base for many years to come. He batted .314 in his first full season as the Cubs won the 1932 pennant. 1934 was the first of 8 seasons that saw Herman selected to the National League All-Star team, and he was one of the most reliable players in the senior circuit. In 1935, he had a league-best 227 hits and 57 doubles as the Cubs rolled to another pennant, but lost the World Series again.

By 1940, Herman's numbers began to wane, and he saw himself traded to the Brooklyn Dodgers for Charlie Gilbert and John Hudson. Aided by a depleted talent pool due to World War 2, Herman rebounded in 1943 to hit .330 (2nd in the NL) but next season, at age 34, he joined the military and missed 1944 and '45.

At 36 years of age, it was unexpected that Herman would return from the war as a player, but he played most of 1946, splitting time between Brooklyn and the Boston Braves, playing second, third and first base. He batted a respectable .298. He was traded to Pittsburgh before the 1947 season, and was named player-manager, although he played in only 15 games hitting a paltry .213. He was also relieved of managerial duties before the end of the season as the Pirates went 61-92 under his leadership. It was not his last day on the bench, but his days at the plater were over. His career totals include a lifetime .304 average and over 2300 hits.

Herman moved on to manage in the minor leagues for a few seasons, until he was brought on by the Dodgers as a coach in 1952, followed by the Milwaukee Braves in 1958. In 1960, he became the third base coach for the Boston Red Sox, and in 1964, was named the Red Sox manager for the last two games of the season as the Sox fired Johnny Pesky. The Red Sox fared no better under Herman in 1965, as they lost 100 games and the Sox finished in 9th. Herman was fired partly through the 1966 season.

Billy Herman was elected into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1975 by the Veterans Comittee. He died in 1992 of cancer.

The Autograph: Herman was a regular through-the-mail signer, as well as a frequent signer at Hall of Fame ceremonies, spring training and conventions. His autograph is very common.

Wednesday, September 1, 2010

Wednesday, May 12, 2010

#32 Terry Moore

Terry Moore was born in 1912 in Vernon, Alabama. Like many Cardinals of his generation, he moved his way through the Cards' farm system and became a member of one of the more notable outfields in baseball history. Teaming with Hall of Famers Stan Musial and Enos Slughter, Moore was a decent hitter as well as an outstanding defensive player.

Moore hit his stride in 1939, batting .294 while being named to the NL All-Star team for the first of four consecutive years. He batted a cumulative .295 from 1939-1942, with 46 home runs, before heading off to fight in the war.

Like so many other players, Moore returned from the World War 2 a shell of player he was. He hung around until 1948, when St Louis released him. He finished with a .280 lifetime average and 1318 hits.

Moore got his chance to manage in 1954, when he took over the Phillies half-way through the season. Replacing Steve o'Neill, the Phils went 35-42 under Moore, and he was replaced by Mayo Smith in 1955. Moore died in 1995.

Not much is written about Moore, at least nothing outside statistical analyses. I did find this sweet pic shown below of Moore modeling an early prototype of a batting helmet. It is hard to be remembered as a good outfielder when you are outshined by the other two outfielders who happen to be great (just ask Davy Jones, Bob Meusel or Duffy Lewis).

The Autograph: In the late 80's and early 90's, Moore enjoyed a resurgence in the hobby as he attended autograph shows along with Stan Musial and Slaughter. He was also one of the first non-HOF or non-HOF-caliber players I wrote to who charged for his autograph. I begrudingly paid the fee for this card.

Thursday, April 22, 2010

#31 George Kelly

George "Highpockets" Kelly was born in 1895 in San Francisco, California. A survivor of the 1906 Earthquake, Kelly was a big fan of the Bay City's PCL club, the Seals. This was an inspiration as he played baseball frequently in his childhood. As a 6'4 teenager, Kelly quickly moved ahead of his classmates, and his natural hitting ability caught the attention of semi-pro clubs around Frisco and Oakland. Fresh out of high school, Kelly signed with Victoria in the NorthWest League in 1915 and quickly caught the attention of John McGraw, manager of the New York Giants. The Giants bought his contract and he was called up to the Giants for a look in late 1915.

After poor performances in limited action for the Giants in 1915 and 1916, Kelly was waived by the Giants shortly into the 1917 season. He was picked up by the Pirates, but faired no better and was let go. McGraw decided to give Kelly another chance, and signed him and sent him to Rochester for the remainder of the 1917 season. Kelly was called on to fight in World War One, and missed the 1918 season. Upom his return to Rochester in 1919, Kelly made the most of his time there and tore up the International League, hitting .356 and 15 home runs. He was poised to return to the National League, but it took a dirty player for him to get his chance.

Hal Chase was the full-time first sacker for the Giants in 1919, and was regarded at the time as the best defensive first baseman the game had ever seen. Chase was no slack at the plate. However, his skill on the field was no match for his lack of moral fiber. Rumors had been floating for years that Chase's ability was "for sale" and was willing to make some side money by throwing games. Rumors had been flying about Chase's corruption as early as 1910. By 1919, the stink surrounding Prince Hal had grown strong, and McGraw called up Kelly to be groomed as Chase's replacement. Kelly responded by hitting .290 in 32 games. After the season, the National League President received an envelope from an anonymous contact, showing a payment from a gambler to Chase to throw a baseball game in 1918. The Giants terminated Chase's contract, and Chase never played in the Major Leagues again.

Kelly became the Giants full-time first baseman in 1920, and lead the league in RBI. He followed that up with a home-run title in 1921, helping the Giants to their first of 4 straight pennants. For the next six seasons, Kelly was the best first baseman in the National League, and one of the game's premier sluggers.

After the 1926 season, he was traded to the Cincinnati Reds for Edd Roush. Although his power numbers were off, mostly due to the change of parks, Kelly still batted around .300 over the next four years, splitting 1930 with the Reds, Cubs, and Minneapolis in the International League. He spent 1931 in the minor leagues, before returning to the National League in 1932, this time with the Brooklyn Dodgers. He was released by the Dodgers following the close of the season, and Kelly headed back west. He played sparingly with the Oakland Oaks of the PCL in 1933 before hanging his glove up for good. Kelly finished his 16-year career with a .297 lifetime average and 1020 RBI.

Kelly bounced around the National League for the next 14 years, picking up coaching jobs for old friends, and after that became a scout for the Reds. He lived in retirement in Millbrae, California. Kelly was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1973, and died in 1984 at the age of 88.

Kelly is often maligned as being one of the worst Hall of Fame selections. Sometimes I think that members of the Veterans Committee thought they were voting for third baseman George Kell (a deserving candidate). He may be one of the weakest selections, but the thing that annoys me most about Kelly being in the Hall of Fame is that he is often posted as the argument for other non-HOF caliber athletes to be inducted (see Hodges, Gil). It is not worth my typing to discuss Kelly's Hall of Fame credentials (or lack thereof). He is in, and he is never getting out. Let's not repeat the mistake by letting in other not-quite-qualified players. Oops. We already did (See Rizzuto, Phil).

The Autograph: Always a great signer. I don't have a lot of Kelly because he died early in my hobby.

#30 Larry French

Larry French was born in 1907 in Visalia, California. He joined the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1929, and from there embarked on a long and successful career, becoming one of the the top lefthanded pitchers in the National League in the 1930's.

After a 7-5 record in his rookie season in '29, he became a mainstay in the Pirates rotation, winning 17 and 15 games before attaining two 18-win seasons in 1932 and 1933. After slumping to 12-18 in 1934, he was traded to the Cubs where his career was resurrected. With a pennant-winning team, French went 17-10 with a 2.96 ERA, but lost two games in the World Series against the Detroit Tigers. He followed that up with an 18-9 record in 1936 and 16-10 in '37.

After a few more solid seasons for the Cubs, French was traded to the Dodgers near the end of the 1941 season. In 1942, at 34 years of age, French went 15-4 with a 1.83 ERA (7 innings shy of qualifying for the league lead) in time split between the bullpen and the rotation.

Following the 1942 season, French found beginning of a new career and a new calling. Already a member of the Navy Reserve Corps, French joined the Navy full-time and never again appeared on the diamond. He won 197 games in his career, and threw over 3100 innings.

French saw action in the D-Day invasion of Normandy in June of 1944, and also found himself in the Okinawa invasion the following year in the Pacific. He was released from active duty in late 1945, and contemplated returning to baseball to get those three wins he needed to get 200, but decided against it. He stayed in the Naval Reserve, and in 1951 he was recalled when the Korean War erupted. After the Korean War, he remained stationed in San Diego, and in 1965 was promoted to Commanding Officer. He retired from the Navy in 1969, and lived in San Diego the rest of his life, playing golf and squash, as well as gardening with his wife, Thelma. French died in 1987 at 79 years of age, and is the only man in baseball history to have served ten years in both the military and Major League baseball.

The Autograph: There was a stretch where French stopped responding to autograph requests through the mail, but not when I got this card signed.

Sunday, March 14, 2010

#29 Stan Coveleski

Born Stanislaus Kowalewski in 1889 in the heart of anthracite country, Stan Coveleski spent his early teen years in the coal mines near Shamokin, Pennsylvania. Working 12 hours a day, six days a week, Coveleski's only recreation during his off-time was throwing rocks at tin cans. After a while, he said, he got so good he could do it blindfolded. When the local school's baseball coach heard about his skill, they asked him is he would like to exchange the rock with a baseball. He was one of five brothers born to his Polish-born parents, four of which played professional baseball. The oldest, Jacob, was killed in the Spanish-American War in 1898. Frank pitched some before rheumatism ended his career. John was a third baseman and an outfielder who never made it out of the minor leagues. That leaves Harry and Stan. Harry Coveleski shaped the 1908 National League pennant race. While with the Phillies, he beat the Giants three times in the last 8 days of the season, probably more at blame for the Giants pennant swoon than Fred Merkle's legendary base-running gaffe. Harry wound up winning 20 games three times for the Tigers in the early 1910's.

After playing around Shamokin, Stan signed with Lancaster in 1909 for $250 a month, a nice raise from his current job of cutting timber, which paid $40 a month. He went 23-11 in his first season with Lancaster, hurling 272 innings. In 1912, he moved to Atlantic City, and his 20 wins there caught the attention of Connie Mack of the Philadlphia Athletics. After a short stint with the Athletics, who had a deep pitching staff at the time, Coveleski was sent to Spokane (Wash.) in the Northwest League for some seasoning. In 1914, Coveleski wa traded for five players to Portland in the PCL. It was in Portland that Coveleski learned a new pitch, a pitch that would make him a Hall of Famer.

Already armed with a good fastball, curve, and off-speed pitch, Coveleski began to fool around with the spitball. The "spitball" is a generic term for a pitch where the ball has been doctored. That can be either a substance used to change to grip or rotation, or scuffed up to get different breaking action. This type of pitch was very legal in the early days of the sport, and those that mastered it counted on it as much as any other "out" pitch. And Coveleski quickly developed one of the best the game has ever seen. He tried out with tobacco juice first, but Iron Joe McGinnity, a spitballer who won an American League record 41 games for the New York Higlanders (aka Yankees) in 1904, suggested he use alum instead. Coveleski kept alum in his mouth while on the mound, and the gummy residue gave his ball some action that was incredibly difficult to hit.

After the 1915 season in Portland, Coveleski was sold to the Cleveland Indians, where he won 15 games in 1916. He won 19 games in 1917, and 1918 was the beginning of four-straight seasons of at least 22 wins.

In 1920, the Indians were set to be in a season-long battle for the pennant. The New York Yankees were in the thick of things for the first time, thanks to their newest acquisition, Babe Ruth. The Chicago White Sox were as good as ever, for most of the team was inspired by the defeat in the World Series before and the rumors that the 1919 Series had been fixed. But the Indians overcame a series of tragedies to win their first pennant and World Championship in one of the greatest pennant races ever.

Cleveland Indian shortstop Ray Chapman was killed in August when a Carl Mays pitched struck him in the head, fracturing his skull. As bad as that was, for Coveleski, it was only an additional event to an already sad season. In May of that year, his wife Mary had died suddenly. Although she had been ill, her health had not deteriorated to where her death was expected. He left the team for a week before returning.

That year Coveleski won 24 games with a heavy heart, while Jim Bagby won 31. That one-two punch carried the Indians to the World Series, but it was Coveleski who was the hero. Coveleski won three games in that World Series, going the distance in all three games he pitched. Only Mickey Lolich has thrown three complete game World Series wins since (1968).

Prior to the 1920 season, the rules of baseball were modified and the spitball was banned. However, 17 pitchers who relied on the pitch were permitted to through the pitch that season, to give them a chance to adapt their skills to other pitchers. However, after the season, it was decided that rather than force these guys to change their abilities, they were allowed to throw the pitch for the remainder of their career. When Burleigh Grimes retired in 1934, he was the last man to legally throw a spitball in the major leagues.

Coveleski's career showed a slight decline after 1921, and after a mediocre season in 1924, Coveleski, now 35, was traded to the Washington Senators. He rebounded in 1925, going 20-5 with an AL-best 2.84 ERA, but the end of the road was quickly approaching. After two more seasons of decline, he was released by the Senators in 1927. He signed with the Yankees and pitched briefly in 1928, but upon his release was the end of Coveleski's days on the mound. He won 216 games in a career that essentially began at 26, with a .602 winning percentage.

Now re-married, to his deceased wife's sister Frances, Coveleski moved his family to South Bend, Indiana. He owned and operated a gas station there, and bought a house that he would live in for over 50 years. The gas station failed in the Depression, so Coveleski retired and would spend the remainder of his days fishing and hunting.

He was elected into the Hall of Fame in 1969, and was a fixture around South Bend. He fell ill with cancer in the early 1980's, and succumbed to the disease in March of 1984, at 94 years of age.

I am a big fan of Stan Coveleski. I was able to write him in the waning years of his life, and also corrosponded with his son, Bill, after Stan's death. Unfortunately, Bill himself died not long after Stan did. A lot of things draw me to Stan. I admire his blue-collar work ethic and his skill. Like him, I am of Polish ancestory, and there are Kowalewski's in my family bloodline, and both our families came over to the in a similar era. Anyone I talk to who knew him say he was exactly what you hope your favorite athelete would be like. He always signed autographs, answered questions, and loved to talk about the game, although he was also quiet and stoic. Bill told me that even as the cancer got really bad, on his good days he would just sit and sign Hall of Fame postcards by the dozens in case he is unable to sign future autograph requests, or in case he gets fan mail after his death. I regret not writing him earlier, he really sounded like an interesting man.

The minor league park in South Bend is named for Coveleski. Known as the "The Cove," the home of the Silver Hawks is the grandfather of the modern ballpark, designed by the same architectural firm that has done Camden Yards and Jacobs Field.

The Autograph: His autograph is in good supply. I have a lot in my collection. This card, among many others. I have Hall of Fame Postcards, photographs, even a signed baseball.

Below is the Lancaster team, circa 1909. Coveleski can be seen in the top row, fourth from the left.

Wednesday, March 3, 2010

#28 Charlie Gehringer

Charlie Gehringer was born in 1903 in the small farming community of Fowlerville, Michigan. He attended the University of Michigan for a year, before being spotted by Detroit Tiger's former outfielder Bobby Veach, who recommended his friend and Tiger manager Ty Cobb sign him. Gehringer left school and in 1924, made his debut with the Tigers after some time in the Michigan-Ontario League. He returned to Toronto in 1925, despite hitting well in his late-season call-up in 1924. By 1926, he joined Detroit to stay.

Over the next 15 years, Gehringer set the standard for second basemen in the American League. After hitting .277 in his first full season in 1926, he hit .300 or better in 13 of the next 14 seasons, with the exception being .298 in 1932. Teaming with Bill Rogell at shortstop, Hank Greenberg at first and Marv Owen at third, he was part of the best infields in major league history, leading the Tigers to two pennants in 1934 and 1935. That infield alone knocked in a record 462 runs in 1934. Gehringer had 60 doubles in 1936, and won the AL batting title (with a .371) and the leagues MVP award in 1937. In 1940, he hit .313 and lead the Tigers to a third pennant in 7 years.

In 1941, at age 38, his numbers dropped off dramatically and after a 1942 season that saw him hit a mere .267, Gehringer decided to join the army. He came from the war in fine physical condition, and toyed around with rejoining the Tigers to try to get the 161 hits he needed to reach 3000, but decided against it. He finished his career with a .320 average and .490 slugging percentage.

Gehringer's life to this point was two things: baseball and his mother. His mother, widowed when Gehringer was young, was in poor health with diabetes and needed someone to look after her, which Gehringer gladly did. This meant Charlie was a bachelor through his playing days, but when his mother passed, Gehringer finally met his bride-to-be, and they were set to wed in 1949. Gehringer was also elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1949, and the induction ceremony was five days before his planned wedding. Rather then tempt fate and allow something to happen while travelling that could delay or postpone his nuptials, Gehringer chose to skip the induction in Cooperstown and stay home to prepare for the wedding. To make up for his absense, Gehringer would be in attendance at every Induction for the next 40 years.

In 1951, Gehringer became the general manager of the Tigers, a position he held through 1953 before resigning. He returned to work full time for his own company, which manufactured fabrics used on automobile seats. He ran the company until selling his interest in 1974. He died in January of 1993 at the age of 89 following a stroke.

He also owned a gas station in Detroit in the 30's.

Much has been written about Gehringer's quiet personality and robot-like skill. He is also one of those guys you never hear a bad word about from anyone. He was always kind and polite, and kept to Teddy Roosevelts credo about walking softly and carrying a big stick. Satchel Paige said he was the toughest out he ever faced, and Bill Rogell told this blogger that Charlie was the kind of guy you wanted all your friends to be like. I remember very well the day he died, and the tributes poured in to the local media from all around even though lots of his contemporaries had already passed. He is on the short-list of great second basemen, along with Collins, Hornsby, Morgan, Alomar....

I knew a girl who was related to Gehringer. She was like a second cousin or something... not close enough to be in the will, but not too distant to have not met him on several occasions. I always thought that was cool be related to ballplayer. I used to tell people I was related to Nemo Leibold. However, since A) my last name is not Leibold and B) no one knows who Nemo Leibold is, no one seemed to care and it did not get me any closer to hooking up with chicks, which is one of the only two reasons to lie in life (the other is money). Maybe being related to Nemo would have got me in with the Gehringer chick, but she kinda looked like Charlie, so with all due respect to the Mechanical Man, I don't look at that as a missed opportunity.

The Autograph: Gehringer has one of the nicest autographs in sports history. Even in age, it stayed nice and steady. He must have passed his penmanship skills on to Rick Ferrell, because you can see similarities in the two.

Thursday, February 25, 2010

#27 Willie Kamm

Willie Kamm was born in San Francisco in 1900, the son of German immigrants. He grew up playing the game in the streets, a game that his parents never truly understood, even as Kamm became a major league player. A skinny kid with a good glove, Kamm signed with Sacramento in the PCL in 1918, but was released after a mere four games. He signed on with the San Francisco club the following year, but could not get his average out of the .230's in two seasons.

In 1920, following the removal of his tonsils, Kamm put on weight, and began to hit the ball with more authority. Hitting better, and now the best third baseman defensively in the PCL, he was sold to the Chicago White Sox in May of 1922 for a then-unheard of sum of $100,000 ($1.3 million in 2010). Kamm joined the Sox in April of 1923, and over the next seven seasons was the best fielding third baseman in the league, if not the best overall. He batted a solid .281 over that stretch, including a career best .308 in 1928.

After a sub-par 1930. Kamm was traded to the Indians for the 1929 batting champ, Lew Fonseca. The trade, initially disliked by Kamm, was a boost to his career. He batted .291 in 1931, and followed that with two more seasons in the .280's.

By spring of 1935, Kamm, now 35 years of age, had slowed considerably, and by May was released by the Indians. In his 14 years, he batted a very commendable .281 with over 1600 hits. He was also retired with the best fielding percentage by a third baseman at the time (.967), a number since passed.

Kamm returned to California after his playing days, managing in the PCL for a few seasons. He enjoyed the boost in fame he received from Lawrence Ritter's book "The Glory of Their Times," published in 1966. He died in 1988 at the age of 88.

Kamm was a sure and steady player, a model of consistency. One of the players who are forgotten once their playing days ended, it is only through Ritter's book that his name is even slightly remembered today. Had there been All-Star games during his playing days, he would have been on the AL squad year-after-year. When I think of Willie Kamm and try to contemporize his fame, the first two names I come up with are Doug Decinces and Roy Smalley. Smalley and Decinces had nice long careers at shortstop and third base, respectively. Most teams in the AL would have considered their addition to be a marked upgrade to what they currently had there. But the second their careers ended..... well, you don't hear many people talking about Roy Smalley and Doug Decinces these days, do you?

Just out of interest on Kamm's defense, here are the career fielding percentage and chances per game between Kamm and Brooks Robinson. Robinson is generally regarded as the best defensive third basemen ever. Although it is hard to really gage defensive ability through statistics, Kamm had more chances per game, and his fielding percentage vs the league (.948 league avg) is the same 19-point difference as Robinson (.952). I am not saying Kamm was better; I've never even seen film of Kamm (if it exists). I am just saying it is an interesting comparison. I'll even throw Graig Nettles into the mix.

Robinson .971 (.952) 3.20

Kamm .967 (.948) 3.28

Nettles .961 (.952) 2.98

Being from Detroit, I hear a lot about how current Tiger third baseman Brandon Inge is great defensively. Yes, he makes some great plays, and most of his errors are throwing errors. But his career numbers don't come anywhere near Kamm or Robinson. Neither does 2009 AL Gold Glove winner Evan Longoria (with his '09 stats only shown)

Inge .958 (.957) 2.88

Longoria .970 (.956) 2.74

I'll let you Jamesian guys interpret that all you want. I realize that other things affect fielding stats (height of infield grass, bunts vs. smashes down the line, equipment, and so on.) I just think it shows that Kamm may have been better than advertised.

The Autograph: Kamm was a great guy to get autographs from through the mail. He loved being remembered, even if it was only from people who read "Glory" and not from people who saw him play.

In the picture below, from the 1931 Tour of Japan, Kamm can be seen in the top row, third from the right.

Top Row, L-R: Rabbit Maranville, Beans Reardon (maybe), Ralph Shinners, George Kelly, Al Simmons, Tom Oliver, Willie Kamm, Doc Knolls (the trainer), Lou Gehrig.

Bottom Row, L-R: Larry French, Lefty Grove, Muddy Ruel (nice socks), Fred Lieb (the writer), Sotaro Suzuki, Lefty O'Doul, Bruce Cunningham, Frankie Frisch, Mickey Cochrane. Herb Hunter is the dude standing over Al Simmons.

Monday, February 22, 2010

#26 Bill Terry

"Memphis" Bill Terry was born in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1898. The product of a broken home, his parents separated when Terry was in his early teens. He was tough and independent, and landed a job in a railyard at age 15. In 1915, Terry signed with the Atlanta Crackers as a pitcher. He moved around the minor leagues over the next few years, pitching and playing first base to keep his powerful bat in the lineup. He even pitched a no-hitter for Newnan in the Ga-Ala League. In 1918, with World War 1 brewing, and his young bride expecting, Terry quit baseball and took a job with a storage battery company in Memphis, where his wife and in-laws lived. Terry took a job with Standard Oil in 1920, and played on the company semi-pro team. It was there that Terry was spotted by Kid Elberfield, who contacted John McGraw. McGraw was passing through Memphis in April of 1922 as the major league teams headed north after spring training. Terry signed with McGraw and the Giants, and was assigned to Toledo.

He joined the New York Giants in 1923, and quickly became one of the league's deadliest hitters as well as one of its smartest players. He batted .319 in 1925, his first full season as the Giants' first baseman. He batted .372 in 1929, but that was just a taste of what was coming. In 1930, he enjoyed his finest season, rapping out a NL-record 254 hits and batting .401, the last player in the senior circuit to bat that high in a season. He followed that season with a .349 and .350 season. After falling to .322, he rebounded to hit .354 in 1934 and .341 in 1935.

Aside from being the last NL player to hit .400, Terry is also known as the man who replaced John McGraw as the manager of the Giants. McGraw stepped down in 1932 (on the same day Lou Gehrig homered four times, thus stealing Gehrig's headlines) and was dead within a year. Terry lead the Giants to a pennant in 1933 and 1936, his last season as a player. He batted .341 lifetime and both scored and knocked in over 1000 runs.

Terry lead the Giants to another pennant in 1937, and remained manager for the Giants through 1941. In retirement, Terry was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1954. A very successful speculator and business man, e moved to Jacksonville, Florida, where opened up a successful car dealership. This allowed him to purchase the Jacksonville AA club, as well as many other business interests. He stayed in Jacksonville for the remainder of his life, dying in 1989 at 90 years of age.

The Autograph: Despite his big stature in his time, Terry always had time for his fans. I like the way he writes his name out: "Wm. H (Bill) Terry". Very offical and proper, with the "Wm." but adds the "Bill" so you know it isn't an autograph of Willy Terry. (PLEASE don't google "Willy Terry"... you will regret it. I know I do.)

#25 Lou Boudreau

Lou Boudreau was born in Harvey, Illinois in 1917. His mother was Jewish, his father was of French descent. A natural athlete as well as scholar, Boudreau attended the University of Illinois and chose to persue athletics as a career. He played professional basketball for a few years in the National Basketball League, but signed with the Cleveland Indians in 1937 and debuted a year later.

A fine hitter and fielder, Boudreau quickly assumed the shortstop role, and became the leader of the Indians on the field. It wasn't long before he became the leader in the dugout, too. In 1942, at the mere age of 24, Boudreau was named manager of the Tribe after Roger Peckinpaugh was promoted to General Manager.

Classified as 4-F by the US Draft Board due to arthritic ankles, Boudreau remained stateside during World War 2 and was one of the American League's premier players. He won the batting title in 1944 with a .327 average and finished 6th in the MVP voting. He did not have a drop-off after the war, and in 1948, had one of the best seasons a man has ever had in the history of the game. Aside from managing Cleveland to their second (and as I write this, last) World Series title, he batted .355 with 18 home runs and was voted the AL Most Valuable Player. By 1950, his problems with his legs took their toll, and depsite a 92-62 record he was both fired as manager and released as a player by Cleveland. He signed the Red Sox in 1951, and played sparingly. He was named manager in 1952 but only played in 4 games, the final ones of his career. He stayed on as manager of the Red Sox until 1954, and then moved to three unsuccessful years at the healm of the Kansas City Athletics. He became the Cubs radio announcer in 1958, but swapped gigs with the Cubs manager Charlie Grimm in 1960. He returned to the radio booth in 1961, where he remained a fixture until 1987.

Boudreau was elected into Baseball's Hall of Fame in 1970. His daughter Sharyn married Denny McLain, who would win two Cy Young Awards for the Detroit Tigers in the 60's. Boudreau wrote an autobiography in the mid-90's, and in August of 2001, he died of complications of an infection and diabetes.

The Autograph: Boudreau's autograph is one of the most common Hall of Fame autographs around. He was always a great signer.

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

#24 Bill Dickey

Bill Dickey was born in 1907 in Bastrop, Louisiana. His father John had played semipro ball, as had his older brother Gus. Bill followed suit with them into the world of baseball, with much more success. His younger brother Skeets would follow Bill to the majors, playing six years himself.

Dickey played on the hometown team as a teen, also starring on the high school team. After high school, he went to Little Rock college where he played football as well as baseball. Dickey signed with the Southern League's Little Rock team, which was unofficially affiliated with the Chicago White Sox. He was moved to the team in Jackson (Mississippi) in 1927 where he continued to produce. However, Jackson waived their rights to Dickey, and he wound up signing with the Yankees. Dickey's time in the Yankees' organization was short lived; he joined the Bronx Bombers in late 1928 at 21 years of age.

By spring of 1929, the Yankees had what they never had: a catcher. In 28 years of existence, the sporadically had catchers that were at best adequate, but for the most part expendable. Dickey started the tradition of great Yankee backstops that would include Yogi Berra, Elston Howard, Thurman Munson and Jorge Posada. He batted .324 in his rookie year of 1929, and would bat over .300 for the next 6 seasons. After a subpar 1935, he rebounded in 1936 to one of the best seasons a catcher on the junior circuit would ever have. He hit .362 with 22 home runs and knocked over 100 runs for the first of four straight seasons. He continued to be the Yankees every-day catcher until 1939. From 1929-1939, he batted .320 and slugged .510.

Dickey, now 33, accepted part-time duties in 1940, and shared catching duties through 1943. He then joined the military for World War 2. He returned to the Yankees in 1946 and played in 54 games, but also was named manager when Joe McCarthy resigned. He finished out the season as manager before.

After spending the 1947 season as a manager in the Southern League, he rejoined the Yankees as a coach, and was instrumental in developing Berra and Howard into the great players they were. He stayed on until 1958, when he left coaching and returned to Little Rock. He remained a scout for the Yankees and also worked at Stephens Inc. brokerage house as a securities representative. He finally retired for good in 1977. He was elected to Baseball's Hall of Fame in 1954, and had his number 8 retired by the Yankees, also worn by Yogi Berra. He was a regular at Yankee Old-Timers Day (You can see Bill at 0:36 and 0:47). He died in 1993 at 86.

For a while there, Dickey was the greatest catcher to ever play the game. Maybe that claim was buoyed by his uniform, but his shear dominance at that position through the 30's put him ahead of Hartnett, Lombardi, Bresnahan and even Cochrane. Since that time, we have had Berra, Bench, Fisk, Rodriguez.... and Dickey's name and feats begin to lose their relevance. Baseball sometimes has a fickle memory.

The Autograph: I was very surprised to get Dickey's autograph. Something I learned about autograph collecting as a kid: When it came to baseball players and their signing habits, Yankees were trickier than non-Yankees. I don't know if that is arrogance, or circumstance. But that is how my teen-aged mind profiled. Dickey signed my cards for me, and I was excited. I knew he had a reputation for not always accomodating requests, but he did for me each time I wrote.

Tuesday, February 9, 2010

#23 Johnny Mize

Johnny Mize was born in 1913 in Demorest, Georgia. As a child, his natural athleticism allowed him to excel in many sports, most notably tennis, but he chose baseball to be what he would dedicate his life to. At age 17, he signed with the St Louis Cardinals and was assigned to Greensboro in the Piedmont League. In 1933, he was batting .360 with Greensboro when he was sent to Rochester in the International League. His 1934 and 1935 were shortened by injury, but the Big Cat could not be kept out of the Natinal League forever. He finally joined the Cardinals in 1936, and the first baseman had immediate impact. He won the batting title in 1939 with a .349 average, as well as topping the league in home runs as well, with 28. In 1940, he belted 43 homers and finished second in the MVP voting for a second straight season.

After the 1941 season, Mize was dealt to the New York Giants, and after a 1942 season that saw him hit .305 with 110 RBI, he joined the military and spent the next three years helping with the war effort. He returned to the Giants in 1946, and 1947, he had career highs in home runs (51) and RBI (138). He added another 40 home runs in 1948 at age 35, and in mid 1949, was sent to the Yankees. He stayed with the Yankees for 5 years, until finally retiring at age 40 in 1953.

After his career ended, with 359 home runs and a .312 lifetime average, Mize had to wait until 1981 to be inducted into the Hall of Fame. He had bypass surgery in 1982, and spent his remaining years back in Demorest. He frequently appeared at Old-Timer games, and spent a lot of his time visiting children's hosptials to sign autographs and tell stories to kids. He died in his sleep in 1993 at the age of 80.

Mize is one of those players whose candidacy for the Hall of Fame seemed so obvious. He missed three prime years due to World War 2, so he would have easily approached 450 lifetime home runs and 2500 hits. An incredible slugger, and a great contact hitter (in the year he hit 51 home runs, he only struck out 42 times). In fact, he only fanned fifty times in a season one (57 in 1937). He attributed his hitting skill to practing hitting a tennis ball with a broomstick for hours as a kid.

My dad took me to the Baseball Hall of Fame for the first time in 1981. We went for induction weekend, to watch Mize, Bob Gibson and Rube Foster get inducted. It was a thrill for me, at age ten, to see this event. I remember hearing the legenday speech by Ernie Harwell as he was inducted into Broadcaster's wing of the Hall. Foster had died 51 years earlier, but his widow (!) accepted the award for him. She reminded me a lot of Mother Jefferson. Mize's speech was a good and heart-warming one, so good that around 20 years later, I lifted part of it for a toast at my friend George's wedding. Mize said, "Years ago, writers told me I'd make the Hall of Fame, so I kinda prepared a speech. But somewhere in the 25 years it got lost." I took that quote and twisted it around a little to mock George's lengthy engagement at their wedding reception.

The Autograph: Mize was always a willing signer, although by the time I got to writing to him, he was asking for 5 dollars each to go to a children's hospital near his home.

Sunday, January 31, 2010

#22 Edd Roush

Edd J Roush was born in 1893 in Oakland City, Indiana. His father William was a locally-reknown baseball player as well as a dairy farmer. Undoubtedly the work young Roush did on the farm lead to his strong hands that allowed him to yield a 48-ounce bat throughout his career.

At age 16, the youngster got his chance to play for the local Oakland City semi-pro club when the regular outfielder didn't show. He got a couple of hits, and the job was his. A natural lefty, Roush had learned to throw with his right hand out of a lack of righthanded gloves available to him growing up. Roush played some second base while with Henderson (Ky) in 1911, but gladly went back to the outfield when the chance arose. In 1912, he moved to the Evansville club in 1912, and was having a great season in 1913 when his contract was sold to the Chicago White Sox in August of the year. After a short stint with the Sox, he was farmed out to the minor leagues on September 11, 1913.

During the off-season, dissatisfied with his contract and his prospects with the White Sox, he jumped to the Federal League and signed with Indianapolis. It was a successful move, for he batted .325 in 79 games (and married that April, too). The Indianapolis franchise moved to Newark for the 1915 season, and Roush batted .298 in a full-time capacity. However, the Federal LEague disintegrated that winter, and Roush was sold to the New York Giants. Dissatisfied over his playing time and his hatred for manager John McGraw, Roush was excited when he was traded to the Reds in mid-season with Christy Mathewson. Roush played well for the Reds down the stretch, and he was on the cusp of a fantastic career as a Red.

He won the National League batting title in 1917, missed by two percentage points the following year, but won another one in 1919 when he lead the Reds to the World Championship over the Black Sox. Roush regularly hit over .300 through 1926, and was a spectacular fielder as well.

After the 1926 season, 33-year old Roush was dealt back to the Giants. He threatened retirement over playing for McGraw, but McGraw, who claimed he had been trying to get Roush back since 1917, assured him things would be different this time around. Roush reluctantly agreed, and he hit .304 for New York in 1927. Injuries began to take their toll. His knees were getting worse, and he also missed a lot of 1928 due to abdominal surgery. He sat out the entire 1930 season due to a salary dispute. He returned to the Reds for the 1931 season before calling it quits for good. He had almost 2400 career hits, and a .323 career batting average (.331 with the Reds.)

Roush coached for a year, for the Reds in 1938, but due to a knack for financial investments, Roush was able to enjoy his retirement, unlike so many teammates who had to find new careers. Roush was elected to Baseball's Hall of Fame in 1962, and in 1969, was voted by the Cincinnati Red fans as the greatest Red player in the franchise's history. (But please note the year... the Big Red Machine was just being pieced together.)

Roush split his retirement time between Oakland City and Bradenton, Florida, where he spent his winters for 35 years. On March 21, 1988, Roush made his way to Bill McKechnie Field, where the Texas Rangers and the Pittsburgh Pirates were to play a Grapefruit League game. Roush was a fixture around the park for many years, chatting it up with players, umpires and fans alike. His visits to the clubhouse were always a treat for Roush, as well as the players. However, before the game began, Roush suffered a heart attack, and died at the field. He was 94 years old.

Roush is known as being an independent and hard-nosed player. He never reported to spring training, and was a regular contract hold-out, too. But at the bat, and in centerfield, his skills were better than anyone in the National League. He was also not afraid of a fight, often spiking infielders after their pitcher had thrown one inside too close... so much so that the infielders would demand their hurler not throw too close to Roush.

Roush was also vocal about the 1919 World Series, and insisted to his dying day that the Reds would have beaten the White Sox either way. He also said that everyone on the Reds knew something fishy was up during the series, and one gambler even approached Reds pitcher Hod Eller in an elevator with an offer to throw games. Roush was the last surviving participant of the Series, and in 1987, he even ventured up to Indianapolis where filmmaker John Sayles was directing a movie based on the 1919 Black Sox book, "Eight Men Out." On the set, Roush regaled the actors and crew with old baseball stories, as well as gave some advice on hitting to the actors. Great movie, you should check it out if you haven't seen it yet.

The Autograph: Roush was one of my favorite old-timers. A true gentleman and class act, he replied to every one of my letters, be it from Indiana or Florida. I can still remember my sadness upon hearing of his passing. I was hoping that he would make it another six weeks to his 95th birthday, so he could pass Elmer Flick as the oldest Hall of Famer ever. (Al Lopez later passed Flick in longevity). Roush was also the last surviving player to have played in the Federal League, the last challenge to the supremacy of the AL/NL.

Monday, January 25, 2010

#21 Joe Sewell

Joe Sewell's baseball career blossomed from the game's worst tragedy, becoming the game's best contact hitter en route to the Hall of Fame.

Sewell was born in 1898, the first of three brothers to play in the Major Leagues. He honed his batting skills as a kid by hitting rocks with a broomstick, Sewell played at the University of Alabama along with Riggs Stephenson, and in 1920, he signed on to play with New Orleans in the Southern Association. He was hitting .289 when a tragedy in New York changed the direction of his life.

The Cleveland Indians were playing the Yankees at the Polo Grounds on August 16, 1920. A Carl Mays fastball came up and in on Cleveland shortstop Ray Chapman, striking him in the head. Chapman died the next day, becoming the only major league player to die from an on-the-field incident. According to witnesses, the ball bounced so far off of Chapman's head the the Yankee third baseman thought Chapman had laid down a bunt. The Indians, in a heated pennant race, pressed Harry Lunte in at shortstop. When Lunte got hurt a few weeks later, the Indians purchased Sewell contract and he made his debut on September 10. Sewell responded by hitting .329 that month, and the Indians won the World Series.

Sewell stayed with the Indians through 1930, and hit below .300 only twice (.299 in '22, .289 in '30). He was released by Cleveland in January of 1931, and was quickly signed by the Yankees. He played two more years there before retiring. After his career, he spent time as a scout, as well as working in public relations for a dairy. He coached the Univeristy of Alabama's baseball team from 1964-1970. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1977, and regularly attended the induction ceremonies. Sewell died in 1990 at the age of 91. His brother Luke had a long and distinguished career in the major leagues, and brother Tommy had a cup of coffee with the Cubs in 1927.

Sewell's accomplishments on the field are legendary. Standing only 5'6, he was one of the most amazing contact hitters in the games history. In over 7200 at bats, Sewell struck out only 114 times, including two seasons where he only struck out 3 times. More amazingly, Sewell used only one bat through his entire 14-year career, a 40 ounce bat modeled after Ty Cobb's bat. He still holds the record for most consecutive games without a strikeout at 115 games.

The Autograph: Sewell was one of the first players I ever wrote to, and it was always a great response. I read a lot about the 1920 Indians, and I was fortunate enough that so many of the stars of that team (Sewell, Bill Wambsganss, Joe Wood and Stan Coveleski) were still alive when I started collecting. Sewell was the last surviving player of Cleveland's first world champions.

Friday, January 22, 2010

#20 Wally Berger

Wally Berger was born the son of a Chicago saloon owner in 1905. In 1910, the family moved to San Francisco, where Berger and his brother Fred took to the game of baseball at an early age.

Berger toiled around the Bay Area semi-pro circuit for five years, working as a carpenter's assistant, before signing with the San Francisco Seals in 1925. After a back injury almost derailed his career, he stayed with the Seals until early 1927, when he headed off to a job in the copper mining industry in Butte, Montana. However, his journey was derailed as he visited with friends in Pocatello, Idaho. He signed with the local team instead of a "normal" job, and became the regular centerfielder for the club. He tore up the Utah-Idaho League, and by August, his contract was sold and he wound up back in the PCL, this time with Los Angeles. He hovered in the Cubs system for two years, and prior to the 1930 season, Berger was sold to the Boston Braves.

As the Braves leftfielder, Berger made his impact immediately. He hit 38 home runs that season, a National League record for a rookie that still stands today. (It was the major league mark until Mark McGwire's rookie total of 49 home runs in 1987.) He also knocked in 119 runs that year, which was a rookie record that lastest until Albert Pujols rookie season in 2001.

Berger was the sole bright spot of the Boston Braves of the 1930's. He played in four All-Star games (1933-36) and lead the NL in home runs and RBI in 1935. His 34 home runs in 1935 was by far the team's best; Babe Ruth, in his final season, hit 6 homers in 28 games, good for second on Boston.

In 1937, Berger was sent to the Giants, where he hit .291 in 59 games. Shortly into the 1938 season the Giants shipped him the Reds, By 1940, the 34-year old Berger found himself playing out the string in Philadelphia with the Philles. By July, his major league career was over.

Berger signed with Indianapolis in the American Association, but hurt his hand and returned home to California. He signed with Los Angeles in the PCL in 1941, but really had no interest in playing below the Major League level. Upon World War 2, Berger joined the Navy. After the war, he scouted for a few years before leaving baseball for good. He worked at the Northrop Institute of Technology until retirement.

Berger died in 1988 after suffering a stroke. He was 83 years old.

I felt sad when Berger lost his RBI record to Pujols. No disrespect to Pujols, but Berger's rookie records were the only thing keeping this fine player from vanishing to the dustbins of history. He really was an exemplary player, and if the Braves were still in Boston, they would think of him as fondly as the Tigers do Greenberg and the Phillies do Klein.

I used to get Berger confused with Wally Moses. I guess it's just the name Wally. You don't see many people named Wally anymore. In fact, there has not been a Wally in the Major Leagues since 2001 (Wally Joyner, for those of you keeping score). But hope springs eternal every year, and maybe 2010 will be the season we see the major league debut of Wally Backman Jr.

The Autograph: Berger always signed for me through the mail, and this card is no exception. An easy to find autograph, starting around 10 dollars.

Monday, January 18, 2010

#19 Phil Cavarretta

Chicago's own Phil Cavarretta joined the Cubs as a local hero, and spent 22 seasons playing in front of his home town, apearing in three World Series and being named the NL's Most Valuable Player.

Born in 1916, Cavarretta attracted the attention of major league scouts early. He signed with the Cubs before even finishing high school, and in his first game with the Peoria club in 1934, he hit for the cycle. He was called up to the Cubs in September of that year, and made his debut two months after of his 18th birthday. In 1935, at 18, he became the starting first baseman for the Cubs. He was the starter for the next three years, before losing his job to more established veterans. He began to split his time between first and the outfield, and became a full-time player in 1941.

With the advent of of World War 2, Cavarretta became a star, and in 1945, he won the National League batting title with a .355 average. He lead the Cubs into the World Series, and was elected the Most Valuable Player of the National League. Although he never hit that high again, he continued to be a dangerous hitter at the plate even as a lot of the stars of the league returned from the War. In 1950, he saw his playing time diminished, and took of the Cubs as player-manager in 1951, He never got the Cubs over .500, and was released/fired in spring training of 1954. He signed with the White Sox that May and played two more years before calling it a career. He finished his 22-year career with a lifetime .293 average, and 23 hits shy of 2000.

He then went to manage in the minors, with stops in Buffalo and Reno some of the cities on his itinerary. After managing Birmingham in 1971, he left to scout for the Detroit Tigers, and became a hitting instructor for the Mets. Cavarretta died in December of 2010 at 94 years of age. He was the last surviving player to have played against Babe Ruth.

Cavarretta is one of the most popular Cubs of all-time. I guess 20 years of playing will do that, especially if you are a home-town boy. He was a young man, quickly thrust into the world of men in the major leagues. Excited to be playing with his idols, he was known for occasionally over-indulging in raviolis in his rookie years, enough to give him stomach-aches that kept him out of the line-up.

The Autograph: Cavarretta's autograph is very common, especially considering he is still going strong at 93 years of age. I remember in the early 90's, when the autograph hobby really took off, more and more players began to charge for autographs through the mail. There was one company who signed on to represent players as an agency, and collect the money through them. They had a long list of people on their roster, like Cavarretta, Marty Marion, Dom Dimaggio, and so on. Then, when a lot of Hall of Famer's were getting popped on income tax evasion for failing to report income from autograph shows, a lot of players went back to signing for free.

Tuesday, January 12, 2010

#18 Charlie Grimm

Charlie Grimm, known as "Jolly Cholly", was a very popular player and manager, and his immense likeability was only slightly better than his play in the field.

Born in 1898 in St Louis, Missouri, Grimm debuted with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1916 at the age of 17, the team for whom he was a batboy as a child. The signing by Connie Mack was the beginning of a playing career that lasted 21 seasons and saw him finish with 2299 hits and a .290 lifetime average.

After short stays in Philly and St Louis, he joined the Pirates in 1920. He played first base for the Pirates for five years, peaking with a .345 average and 99 RBI in 1923, both totals would be his career high. He was traded to the Cubs after the 1924 season, and it was here that he made his mark. He was the club's first bagger for 8 years, and was one of the most recognizable and well-liked players on the club. He was even given the job as manager in 1932, a job he held until 1938, two years after the closing of his playing career. He batted .364 in two World Series.

Grimm went into business with Bill Veeck in 1941, buying the Milwaukee club of the American Association. He managed the club, and also entertained the fans by playing the banjo for them on occasion. Grimm returned to manage the Cubs in 1944, and managed the Braves from 1952-56. He had one last stint as manager for the Cubs in 1960, and one ended like to other managerial helm had before. Shortly into the 1960 season, Grimm and Cubs Broadcaster a former shortstop Lou Boudreau traded jobs, with Grimm going to the radio booth. After finishing out the season, he returned back to the Cubs playing field as a coach, and soon moved into the front office. He stayed on staff for the Cubs for the rest of his life, his last position being as special assistant to manager Dallas Green.

Grimm died in November of 1983 of cancer in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Grimm is one of those guys where everyone who knew him had a story about his good nature and generosity. There is one tale when Grimm was coaching third on a particularly lackluster afternoon. Marvin Rickert belted a drive to right, and was easily headed to third with a stand up triple. Grimm frantically waved Rickert around and motioned for him to hit the dirt at third base. As Rickert slid into the bag, he was greeted by Grimm, who was sliding into the bag from the other direction.

The Autograph: Grimm autographs can be found for 10 dollars and up. He regularly signed through the mail and at Wrigley Field, as well as Spring Training.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)