Born Stanislaus Kowalewski in 1889 in the heart of anthracite country, Stan Coveleski spent his early teen years in the coal mines near Shamokin, Pennsylvania. Working 12 hours a day, six days a week, Coveleski's only recreation during his off-time was throwing rocks at tin cans. After a while, he said, he got so good he could do it blindfolded. When the local school's baseball coach heard about his skill, they asked him is he would like to exchange the rock with a baseball. He was one of five brothers born to his Polish-born parents, four of which played professional baseball. The oldest, Jacob, was killed in the Spanish-American War in 1898. Frank pitched some before rheumatism ended his career. John was a third baseman and an outfielder who never made it out of the minor leagues. That leaves Harry and Stan. Harry Coveleski shaped the 1908 National League pennant race. While with the Phillies, he beat the Giants three times in the last 8 days of the season, probably more at blame for the Giants pennant swoon than Fred Merkle's legendary base-running gaffe. Harry wound up winning 20 games three times for the Tigers in the early 1910's.

After playing around Shamokin, Stan signed with Lancaster in 1909 for $250 a month, a nice raise from his current job of cutting timber, which paid $40 a month. He went 23-11 in his first season with Lancaster, hurling 272 innings. In 1912, he moved to Atlantic City, and his 20 wins there caught the attention of Connie Mack of the Philadlphia Athletics. After a short stint with the Athletics, who had a deep pitching staff at the time, Coveleski was sent to Spokane (Wash.) in the Northwest League for some seasoning. In 1914, Coveleski wa traded for five players to Portland in the PCL. It was in Portland that Coveleski learned a new pitch, a pitch that would make him a Hall of Famer.

Already armed with a good fastball, curve, and off-speed pitch, Coveleski began to fool around with the spitball. The "spitball" is a generic term for a pitch where the ball has been doctored. That can be either a substance used to change to grip or rotation, or scuffed up to get different breaking action. This type of pitch was very legal in the early days of the sport, and those that mastered it counted on it as much as any other "out" pitch. And Coveleski quickly developed one of the best the game has ever seen. He tried out with tobacco juice first, but Iron Joe McGinnity, a spitballer who won an American League record 41 games for the New York Higlanders (aka Yankees) in 1904, suggested he use alum instead. Coveleski kept alum in his mouth while on the mound, and the gummy residue gave his ball some action that was incredibly difficult to hit.

After the 1915 season in Portland, Coveleski was sold to the Cleveland Indians, where he won 15 games in 1916. He won 19 games in 1917, and 1918 was the beginning of four-straight seasons of at least 22 wins.

In 1920, the Indians were set to be in a season-long battle for the pennant. The New York Yankees were in the thick of things for the first time, thanks to their newest acquisition, Babe Ruth. The Chicago White Sox were as good as ever, for most of the team was inspired by the defeat in the World Series before and the rumors that the 1919 Series had been fixed. But the Indians overcame a series of tragedies to win their first pennant and World Championship in one of the greatest pennant races ever.

Cleveland Indian shortstop Ray Chapman was killed in August when a Carl Mays pitched struck him in the head, fracturing his skull. As bad as that was, for Coveleski, it was only an additional event to an already sad season. In May of that year, his wife Mary had died suddenly. Although she had been ill, her health had not deteriorated to where her death was expected. He left the team for a week before returning.

That year Coveleski won 24 games with a heavy heart, while Jim Bagby won 31. That one-two punch carried the Indians to the World Series, but it was Coveleski who was the hero. Coveleski won three games in that World Series, going the distance in all three games he pitched. Only Mickey Lolich has thrown three complete game World Series wins since (1968).

Prior to the 1920 season, the rules of baseball were modified and the spitball was banned. However, 17 pitchers who relied on the pitch were permitted to through the pitch that season, to give them a chance to adapt their skills to other pitchers. However, after the season, it was decided that rather than force these guys to change their abilities, they were allowed to throw the pitch for the remainder of their career. When Burleigh Grimes retired in 1934, he was the last man to legally throw a spitball in the major leagues.

Coveleski's career showed a slight decline after 1921, and after a mediocre season in 1924, Coveleski, now 35, was traded to the Washington Senators. He rebounded in 1925, going 20-5 with an AL-best 2.84 ERA, but the end of the road was quickly approaching. After two more seasons of decline, he was released by the Senators in 1927. He signed with the Yankees and pitched briefly in 1928, but upon his release was the end of Coveleski's days on the mound. He won 216 games in a career that essentially began at 26, with a .602 winning percentage.

Now re-married, to his deceased wife's sister Frances, Coveleski moved his family to South Bend, Indiana. He owned and operated a gas station there, and bought a house that he would live in for over 50 years. The gas station failed in the Depression, so Coveleski retired and would spend the remainder of his days fishing and hunting.

He was elected into the Hall of Fame in 1969, and was a fixture around South Bend. He fell ill with cancer in the early 1980's, and succumbed to the disease in March of 1984, at 94 years of age.

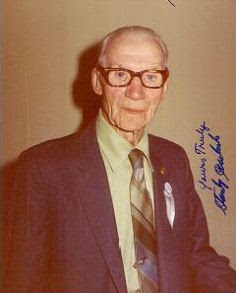

I am a big fan of Stan Coveleski. I was able to write him in the waning years of his life, and also corrosponded with his son, Bill, after Stan's death. Unfortunately, Bill himself died not long after Stan did. A lot of things draw me to Stan. I admire his blue-collar work ethic and his skill. Like him, I am of Polish ancestory, and there are Kowalewski's in my family bloodline, and both our families came over to the in a similar era. Anyone I talk to who knew him say he was exactly what you hope your favorite athelete would be like. He always signed autographs, answered questions, and loved to talk about the game, although he was also quiet and stoic. Bill told me that even as the cancer got really bad, on his good days he would just sit and sign Hall of Fame postcards by the dozens in case he is unable to sign future autograph requests, or in case he gets fan mail after his death. I regret not writing him earlier, he really sounded like an interesting man.

The minor league park in South Bend is named for Coveleski. Known as the "The Cove," the home of the Silver Hawks is the grandfather of the modern ballpark, designed by the same architectural firm that has done Camden Yards and Jacobs Field.

The Autograph: His autograph is in good supply. I have a lot in my collection. This card, among many others. I have Hall of Fame Postcards, photographs, even a signed baseball.

Below is the Lancaster team, circa 1909. Coveleski can be seen in the top row, fourth from the left.